By Judy Scott Feldman, PhD

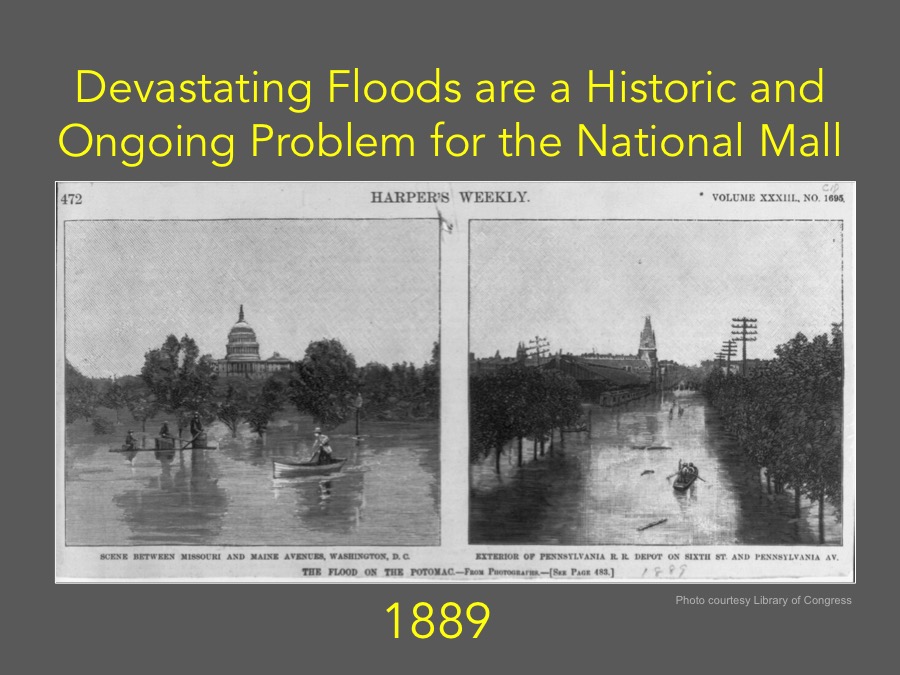

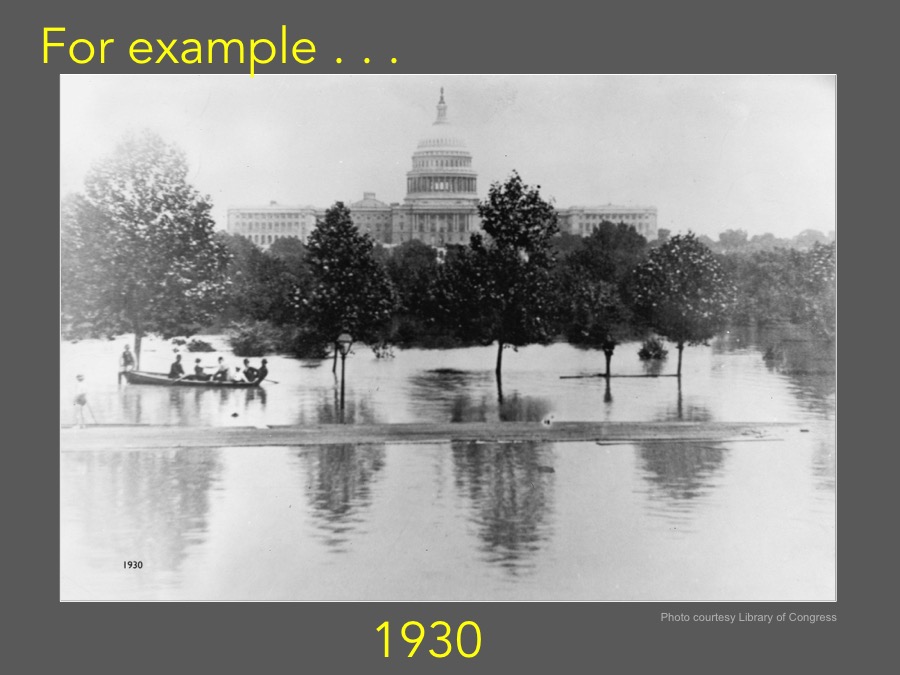

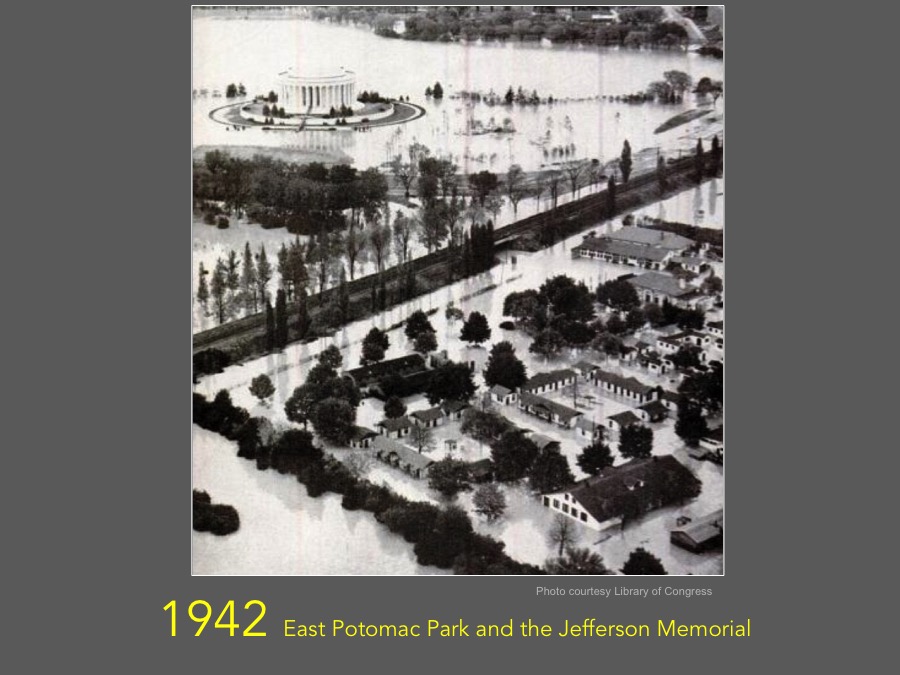

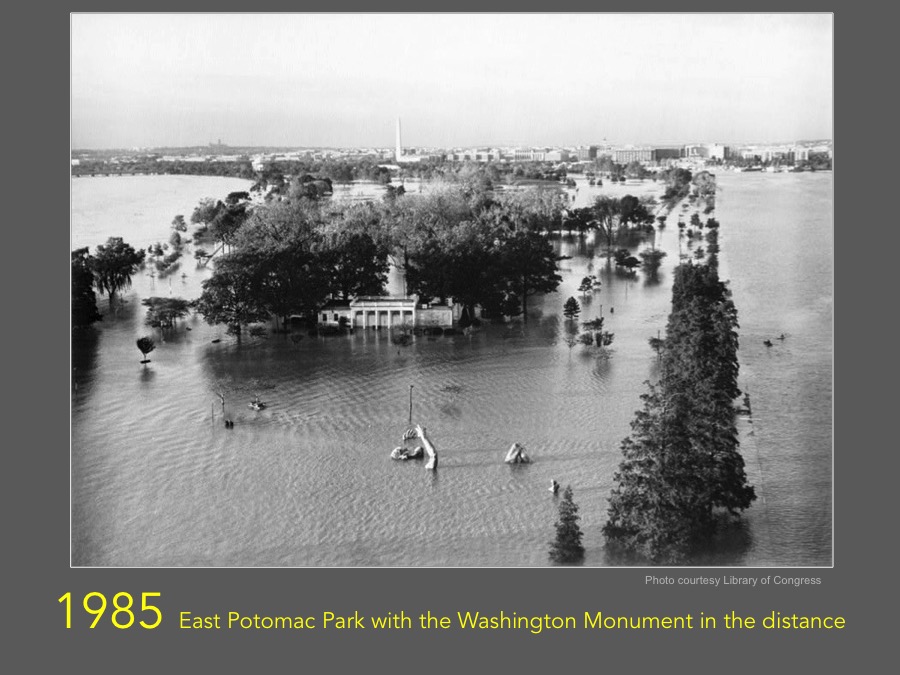

Hurricane season spared Washington DC in 2023 but we can’t expect such good luck indefinitely. As federal and DC officials well know, flooding represents an existential threat to our nation’s capital and the National Mall at its heart. While some steps are being taken, for example DC Water’s construction of stormwater tunnels, there is no unified plan to solve the city’s multi-faceted flooding problem, and unfortunately no urgency to create one.

We are reminded of our failure by a recent article highlighting the flood control successes in Hoboken, New Jersey.

In 2012 Hurricane Sandy slammed head on into New York City and New Jersey, flooding the subway systems and otherwise causing death and destruction. As reported in The New York Times, the city of Hoboken responded by taking an integrated approach to the dual threats of storm surge and heavy rains. It not only strengthened seawalls against rising tides, as New York City did. It invested in green infrastructure and installed large capacity cisterns under city parks to collect storm water. While these improvements didn’t end all the threat, they have proved effective in mitigating flooding and helping the community recover quickly.

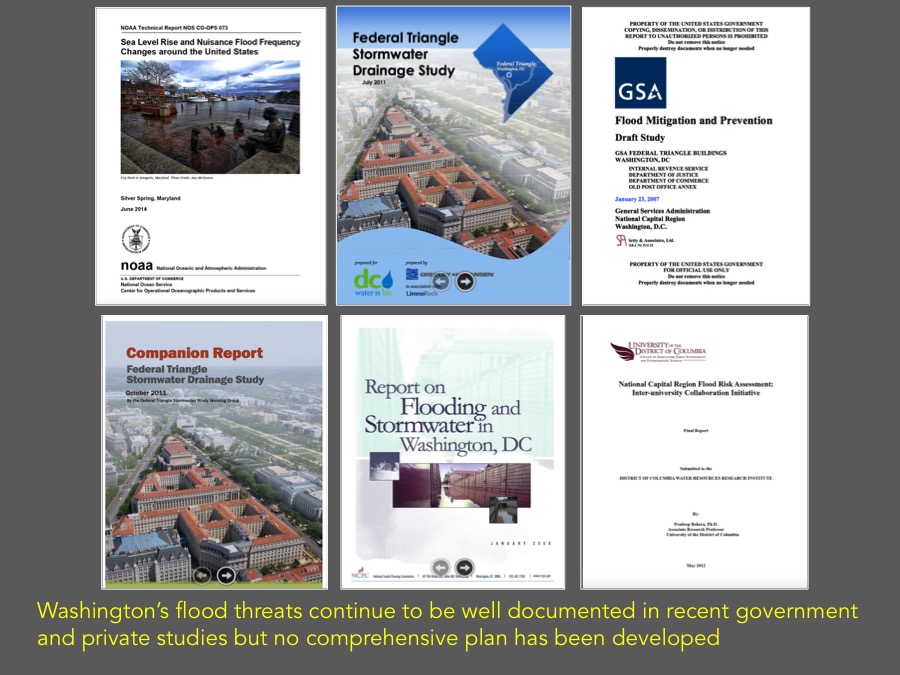

Washington’s flood threats are at least as dire as Hoboken’s but have elicited no similar sense of urgency and collaborative problem solving.

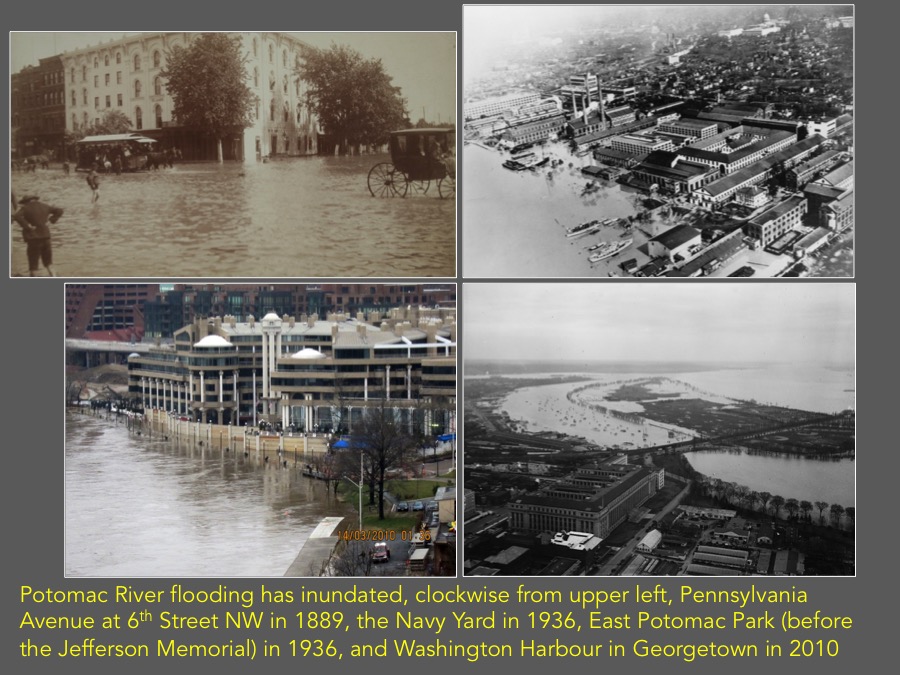

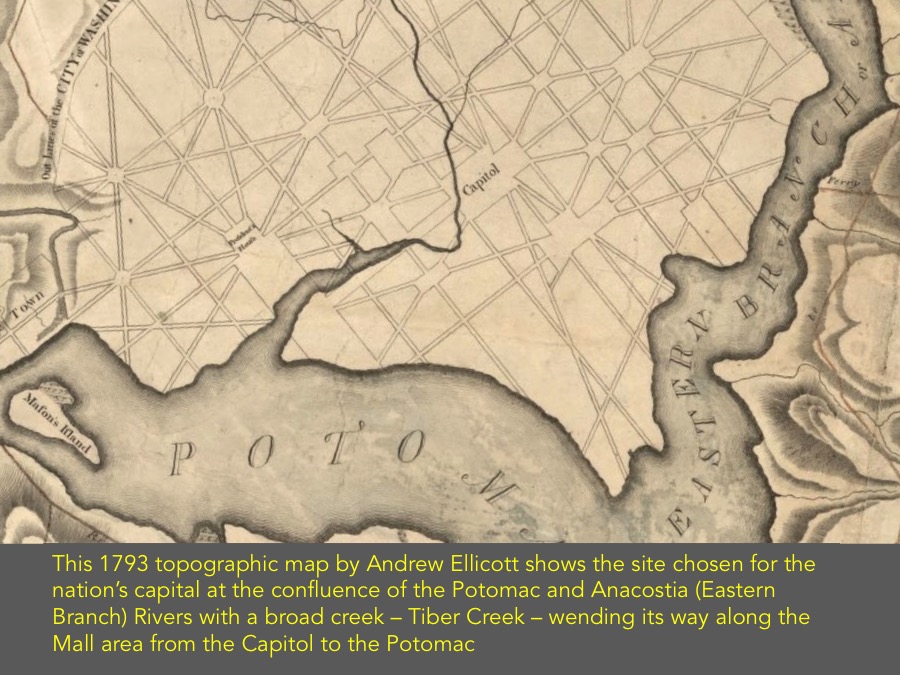

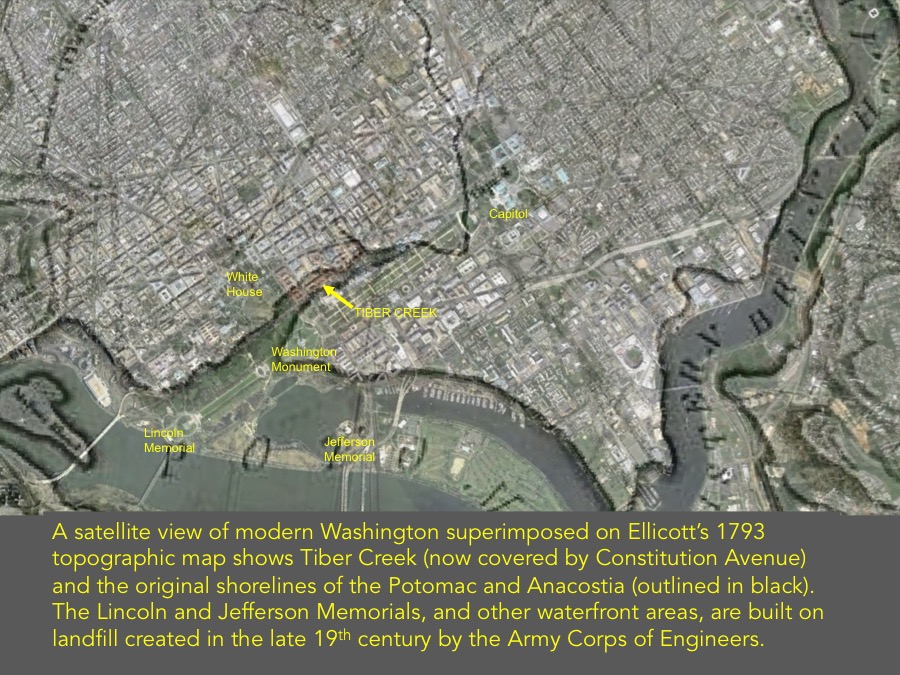

The Potomac River frequently floods low-lying areas of the capital after heavy rains. A second threat is high tide. Almost daily high tides swamp the walkways around the Tidal Basin’s cherry trees, the Jefferson Memorial, and the FDR Memorial. The National Park Service has recently gained approval from review agencies to go ahead with plans to repair and raise the height of a portion of the seawall near the Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials. But is “improving” 19th century seawalls any more than a band-aid solution to the threat of extreme weather events – at a cost of millions to taxpayers? With only one section of seawalls being raised, won’t the floodwaters simply divert around them to further inundate the unprotected areas? Climate scientist testimony during project review by the National Capital Planning Commission answered “no” to the first question, “yes” to the second.

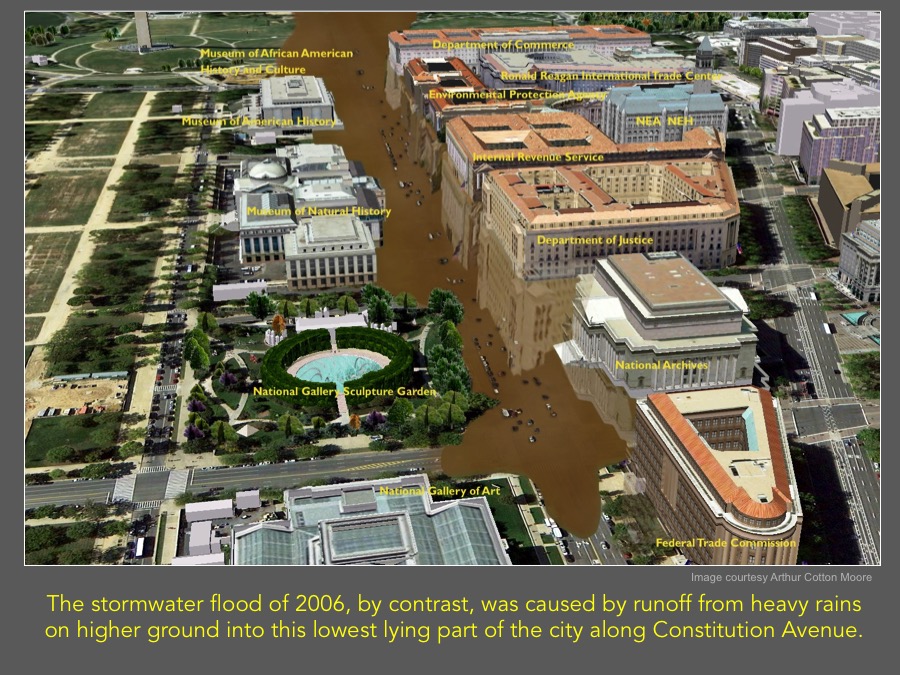

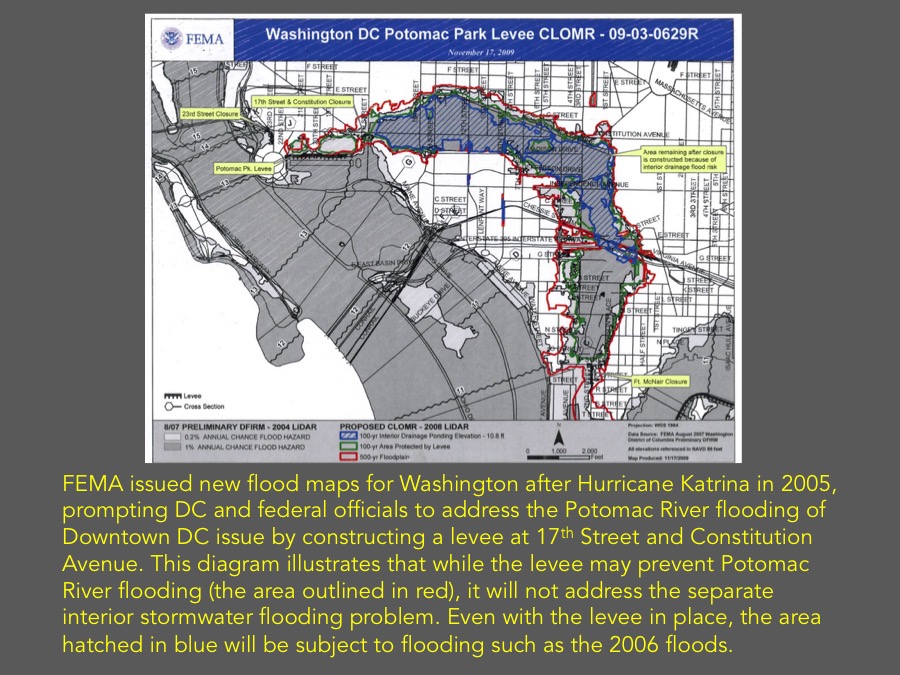

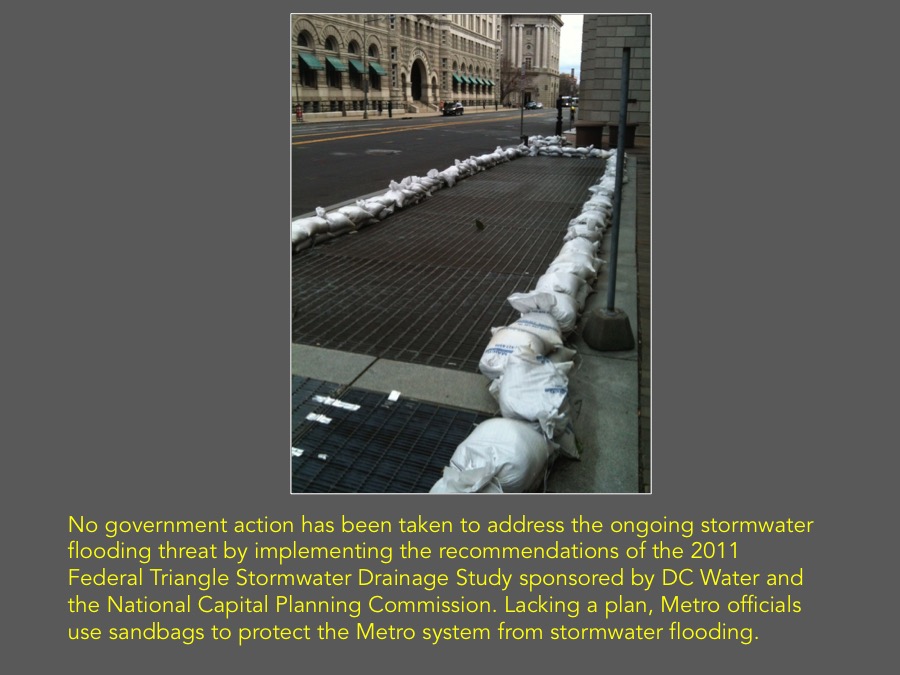

Stormwater is a third threat. In 2006, three days of heavy rain overloaded stormwater drains in the National Mall and Federal Triangle area. Smithsonian museums and the National Archives were inundated with flood water. Government offices and museums had to be vacated for months during clean up and repair. Smithsonian curators are acutely concerned about the ongoing dangers to our nation’s treasures.

Federal and DC agencies, realizing that stormwater flooding will likely increase in frequency and intensity in the future, formed an inter-governmental DC flood group, the DC Silver Jackets team, to study a number of solutions. But in the end they considered their findings “inconclusive” and any potential solution too expensive to act on. So close to two decades on, a shrug (and a prayer?). Why is there no urgency by responsible parties to protect our nation’s monuments, public buildings, and national treasures from another 2006 event?

Hoboken’s chief resiliency officer Caleb Stratton gets to the heart of the problem. In most American cities, he says, “all the infrastructure we create to handle water – roads, sidewalks, sewers – is overseen by different departments with different priorities, none of them specifically responsible for storms. There is no dedicated authority or budget for storm water in most cities.”

And it’s worse in Washington than in other American cities. Who’s in charge? DC Government but also Congress, the Smithsonian and the National Park Service – everyone and no one. DC’s Chief Resilience Officer has no authority over the affected federal lands.

In this maelstrom, citizen groups have little chance to be taken seriously. When our nonprofit National Mall Coalition proposed a comprehensive stormwater solution — the National Mall Underground floodwater cistern-geothermal-bus parking-visitor center facility – there was at first no one to evaluate the project objectively. Eventually, the Army Corps of Engineers prepared a report but their positive evaluation was ignored. Government overseers dismissed the Underground concept because it came from an “outside” group or was considered to be too “ambitious” and complicated (because it required cooperation among multiple government entities).

The need for an integrated approach to flood control in Washington is at least as strong as it is in Hoboken. Each type of flooding – stormwater, Potomac River, tidal – poses a serious threat. In the event of a storm like Hurricane Sandy, all three could occur simultaneously, with catastrophic effects on our monuments, public buildings, and aging infrastructure. Washington narrowly missed a hit from Sandy but our luck won’t hold out forever.

Americans, our capital city, and our Mall deserve better. It’s time to create a Chief Resilience Officer for Washington with the authority to demand collaboration among all responsible parties, to lead a team of climate scientists, flood control engineers, civil engineers, and Washington and Mall historians to create an integrated flood plan and ensure resiliency far into the future.

Hoboken, thank you for showing proof of concept.

• Judy Scott Feldman, PhD, is chair of the National Mall Coalition.