February 2025

Reading of the recent death of Friedrich St. Florian, architect of the National WWII Memorial on the National Mall, I was drawn back to the controversy over that monument that led to creation of the nonprofit National Mall Coalition in 2000. I now come to the rueful conclusion 25 years later that not much has changed or improved in the memorial building process that too often leads to disappointing results. Isn’t it time to rethink how we memorialize America’s history on the Mall?

I met St. Florian first as a then-college professor testifying against what I, like so many critics, felt was a desecration of the Mall open space, and of the oval-shaped Rainbow Pool that was a design component of the Lincoln Reflecting Pool. St. Florian surprised me during the long review process by inviting me personally to see his evolving design in advance of upcoming hearings. He was gracious in listening to my comments and questions, even as my opinion did not change.

The truth was, Florian’s design competition-winning concept did not win design review approval; his revised designs abandoned the original components and meaning; and the final memorial built – after Congress stepped in to assert the monument shall be built with whatever design was on the table – was missing what St. Florian called the still-to-be-decided “central sculptural element.”

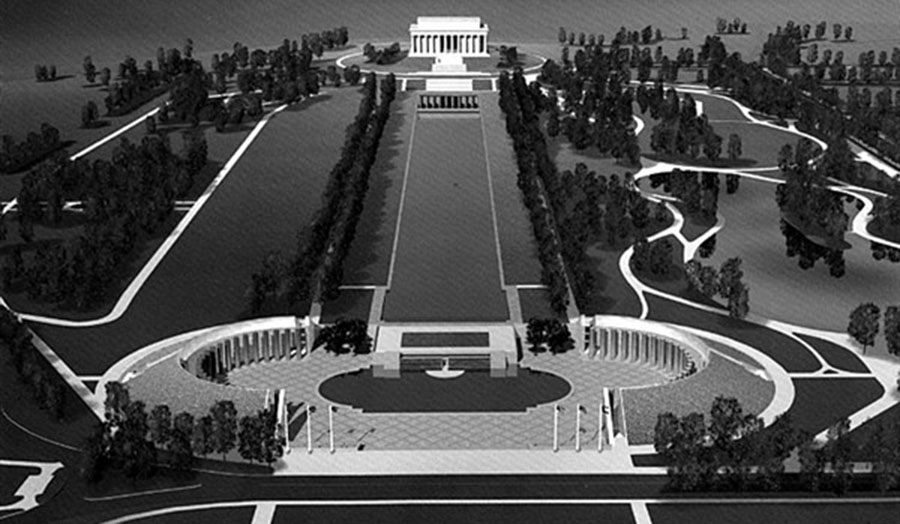

Florian had won the memorial design competition in 1997. But his original concept featuring forty-foot tall columns was rejected by both design review bodies, the Commission of Fine Arts and the National Capital Planning Commission, as too intrusive on the sensitive Mall open space between the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial.

His revised 1998 design, a sunken plaza topped by a metal railing and two stone triumphal arches, deferred to the Mall site but was derided as too tame. World War II, critics said, “was not a walk in the park.” The cenotaph and eternal flame in the western wall, which one architect humorously characterized as “Lincoln on sterno” and others called “the cemetery on the Mall,” was dropped in 1999 and replaced by a wall of 400 stars (each representing one hundred dead).

The revised 1999 concept raised up the 50 square pillars decorated with wreaths and inscribed with names of the states. Criticism continued unabated and three local nonprofits filed a lawsuit. But Bob Dole became spokesman for the memorial and Tom Hanks was enlisted to raise public support and donations. In the end, Congress decided to step in and demanded the memorial be built as designed, effectively nullifying the lawsuit – and infuriating many WWII veterans who argued that the rule of law was what they had fought for against the Nazis.

Could the memorial, the memorial process, be saved? Sadly, no. As Congress stepped in, St. Florian’s design still awaited his decision about a central sculptural element that would give cohesive meaning to the walls and pillars and stars. It was not to be. St. Florian in the end never decided what that crucial central element might be. And that explains the design and conceptual hole in the middle of what should have been a powerful monument to American faith in democracy.

Despite all the controversy, no one disputed the appropriateness of creating a WWII Memorial. And the original stated purpose of the memorial (as provided in the design competition guidelines) – to celebrate not only victory but to honor ordinary Americans including women and children who came together in the national effort – seemed in keeping with the meaning of the Mall.

But in the end, the convoluted design review process, the loss of the original purpose for the memorial, and Congress’s intervention to stop public legal action resulted in a disappointing, confusing, and disruptive memorial that, while loved by many, altered forever the public open space and vistas connecting our monuments to Washington and Lincoln.

Unfortunately, the memorial building process is little changed today. And each new memorial seems to spawn new controversy. Surely, for the sake of our beloved National Mall and its powerful role in inspiring pride and respect for our founding principles, and for serving the American people as the Stage for American Democracy, we can improve that process. We need to ask, what chapters in the American story should be added to the Mall? How can we locate new memorials and museums to reinforce the Mall’s civic purpose? Can we improve the design review process to ensure memorials add to, not detract from, the inspired meaning of the Mall? How can we rise above political fashion to reinforce the brilliant historic plans that made this landscape the beloved, meaningful place it is in American civic life?

Founders of the National Mall Coalition (then known as the National Coalition to Save Our Mall) came together in 2000 – architects, historians, planners, concerned citizens – to bring public input into a process that had proven to be broken. We didn’t oppose honoring WWII veterans, rather how the design process played out. We continue to believe there are serious questions to assign to a new Mall Commission – a 3rd Century Mall Commission – to discuss, debate, and engage the American public in seeking answers.

Visit our archive of the World War II Memorial controversy. Read about the 3rd Century Mall Commission concept.